Mahmoud Darwish was one of the Arab world’s most celebrated poets. For many he was the poetic voice of the Palestinian people, their spokesman and their witness.

Mahmoud Darwish was one of the Arab world’s most celebrated poets. For many he was the poetic voice of the Palestinian people, their spokesman and their witness.

When Darwish died in 2008, he left behind a body of work unsurpassed in beauty and scope. Yet much of the ignition behind his work had little to do with beauty, documenting, as it so often did, one political and humanitarian tragedy after another. His books are testaments to the deepest forms of human suffering. But they are more besides. What made Darwish such a towering presence in Arabic literature was his ability to transform carnage, to transfigure violence, to make the hell of his own private exile a matter of public concern.

Darwish’s peripatetic exile began in 1948 when he was forced from his home in Al Birwah, the village in which he was born, and fled with his family to Lebanon. They returned a year later only to find their home and village destroyed. “We lived again,” he wrote, “this time as refugees in our own country.” Darwish was to re-enact and relive the trauma of these early years throughout his poetic life:

They fettered his mouth with chains,

And tied his hands to the rock of the dead.

They said: You’re a murderer.

They took his food, his clothes and his banners,

And threw him into the well of the dead.

They said: You’re a thief.

They threw him out of every port,

And took away his young beloved.

And then they said: You’re a refugee.

His first book, Bird without Wings, was published when he was 19. Written in the 1960s, it was a decade in which Darwish was frequently imprisoned and lived repeatedly under house arrest. Dispossession and resistance form the core of his disturbing poetic world. It was followed by Leaves of Olive Trees (1964), Lover from Palestine (1966), and End of the Night (1967), the last, his response to the six-day war of June 1967. Darwish was already a member of the Israeli Communist Party and editor of its militant newspaper Al Ittihad. By 1971 he was in Cairo editing the paper Al Ahram and two years later he joined the PLO, a move that resulted in him being refused re-entry into Israel. And so began 26 years of exile.

Darwish’s early poetry bristled with anger at the outrage and injustices of Israeli military occupation and became a potent symbol of resistance. His reputation as a militant poet was one he often regretted. “I don’t decide to represent anything except myself,” he said. Over the next 40 years his poetry moved slowly but steadily away from the openly political and became increasingly introspective. Of his 20 or more books, relatively little poetry has made its way into English.  Fady Joudah’s 2007 translation, The Butterfly’s Burden, the complete 3-book cycle of The Stranger’s Bed (1998), A State of Siege (2002), and Don’t Apologize for What You’ve Done (2003), is the most recent addition and arguably the most generous.

Fady Joudah’s 2007 translation, The Butterfly’s Burden, the complete 3-book cycle of The Stranger’s Bed (1998), A State of Siege (2002), and Don’t Apologize for What You’ve Done (2003), is the most recent addition and arguably the most generous.

Completed in Ramallah shortly after returning to his native Galilee, The Stranger’s Bed surprised and alienated many of Darwish’s readers. It was, unashamedly, a book of love, but as Joudah notes, ‘here he was singing about love as a private exile, not about exile as a public love.’ It’s a book of tender, subtle metaphysical lyrics, with roots in the centuries old tradition of Arabic love poetry:

In me, as in you, a land on the edge of land

populated with you or with your absence. I don’t know

the songs you sob, as I pass

through your fog. So let land be

what you gesture to… and what you do

Darwish was addressing a Palestine on the verge of statehood, and these were poems that appealed for healing of the self and for dialogue with ‘the other’ as necessary pre-requisites for state building:

And it is enough, to know my faraway self, that

you return to me the poem’s lightning when I split

into two within your body

I am yours as your hand is yours

so what’s my need for my tomorrow

after this journey?

But the journey toward that mystical union of selves and others, no less than the forging of a new Palestinian consciousness, was brutally curtailed in the violence of the second Intifada. Darwish, still living in Ramallah, witnessed those terrible events firsthand. The compressed lyrics of A State of Siege speak out of those dark days, from a ‘country on the verge of dawn.’ Twenty years earlier it was another city, Beirut, and another siege that exalted Darwish to his epic masterpiece Praise to the High Shadow (A Documentary Poem). The parallels were unmistakable.

The poems of Don’t Apologize for What You’ve Done continued Darwish’s incessant struggle to continue poetry’s dialogue, to salvage for the exiled voice its right to avenge absence with song. In the book’s final poem, ‘The Kurd Has Only the Wind’, we are returned to his perennial meditations on language, identity and homeland:

…My identity is my language. I … and I.

I am my language. I’m the exile in my language.

…

With language you overcame identity,

I told the Kurd, with language you took revenge

on absence

Darwish spoke to us of a place in time, out of the timeless non-place of exile. His was, so often, a voice among the ruins. His courage reached beyond his own history and geography in art of perpetual transformation and renewal. ‘Tell me how you lived your dream in some place,’ he said, ‘and I’ll tell you who you are.’ It was Darwish’s great gift of telling that made his own nightmare liveable, and it was the indelible prints he left in the language that marked his place and told us who he was.

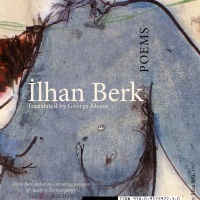

George Messo

First published in Turkish Book Review, No. 5, 2006.